|

| Views from Bukit Jambul, en route to Besakih where the Mother Temple is located. |

|

|

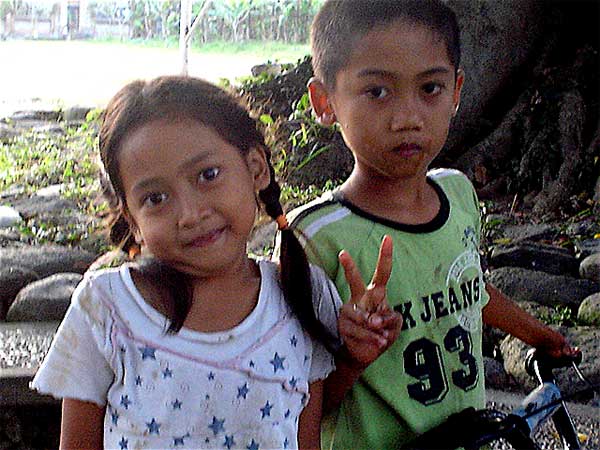

| Bali's biggest temple at Besakih was acrawl with pilgrims when I arrived, so I chatted with a couple of luminously beautiful vendors and rode off into the sunset. |

I GOT AS FAR AS the side entrance to Tirta Empul hotsprings but decided to give it a miss. Too many day-trippers there, it felt like Batu Caves. I figured, the hot springs may be “holy” but, heck, all springs are – and I don’t like humans building a fence (and bureaucracy) around them and charging admission for Nature’s gift of healing.

I GOT AS FAR AS the side entrance to Tirta Empul hotsprings but decided to give it a miss. Too many day-trippers there, it felt like Batu Caves. I figured, the hot springs may be “holy” but, heck, all springs are – and I don’t like humans building a fence (and bureaucracy) around them and charging admission for Nature’s gift of healing.Fifteen minutes later I was feeling exhilarated as the road’s gradient subtly began to increase and I knew I was heading into the highlands. Guess my lungs have acquired a taste for crisp mountain air from fifteen years of living at the foot of the Titiwangsa Range. Stopped to buy half a kilo of heavenly marquisas (“the famous Indonesian passion fruit”) and snapped this portrait of a fresh-faced highland girl (I was charmed by the way the fruits were displayed in elegant pyramids).

|

| Village girl at fruit stall 20 minutes from Gunung Batur |

The volcanic Gunung Batur, reminiscent of Mount Doom in Mordor, its western slope still black, barren and baking hot, while its eastern slope facing Batur Lake is starting to green out beautifully.

The volcanic Gunung Batur, reminiscent of Mount Doom in Mordor, its western slope still black, barren and baking hot, while its eastern slope facing Batur Lake is starting to green out beautifully.

Just as you will meet Wayans, Mades, Nyomans, and Ketuts in every family wherever you go in Bali, the same rule applies to cultural forms and human behavior. Put another way: one fruit stall (like a fresh-faced, smiling village girl) is pretty much the same as another, with minor variations that allow for a degree of diversity – yet, in essence, it is a repeat pattern of a particular motif which generates a dynamic interplay between uniqueness and universality.

Just as you will meet Wayans, Mades, Nyomans, and Ketuts in every family wherever you go in Bali, the same rule applies to cultural forms and human behavior. Put another way: one fruit stall (like a fresh-faced, smiling village girl) is pretty much the same as another, with minor variations that allow for a degree of diversity – yet, in essence, it is a repeat pattern of a particular motif which generates a dynamic interplay between uniqueness and universality.The fractal principle holds true whether in the case of homestays, bakso stands, pirate DVD outlets, surfer beaches, winding mountain roads, dusty and noisy urban streets, night markets, or busloads of daytrippers. However, on an island the size of Bali, the micro- and macrocosmic dance is clearly visible – just as it’s easier to understand the behavior of a small group of individuals rather than that of a mass of faceless statistics.

When one begins to notice the fractal forms at the core of all structures, whether man-made or natural, the effect is somewhat psychotropic. Sensory impressions begin to interlock like pieces of an immense, multi-dimensional jigsaw and the concept of morphogenetic fields suddenly becomes a vivid reality.

You could say the web of life that has been there all the while spontaneously comes into sharp focus, and it seems totally incredible that you never noticed it before. Indeed, this sort of epiphany is akin to the enhanced perception triggered by consciousness-altering substances like psilocybin or lysergic acid diethylamide.

You could say the web of life that has been there all the while spontaneously comes into sharp focus, and it seems totally incredible that you never noticed it before. Indeed, this sort of epiphany is akin to the enhanced perception triggered by consciousness-altering substances like psilocybin or lysergic acid diethylamide.In Bali, the boundary between the secular and the spiritual is blurry to the extreme. Science can be found living happily next door to mysticism. Indeed, I know of no other place where simplicity and sophistication get along so well.

The friendliness and warmth of people you encounter wherever you go is offset - and complemented - by the savvy and sophistication of the Balinese mind.

|

| A pair of mammoths guard the 372 steps leading to the royal pura of Gunung Kawi |

The entire world is drawn to the ultimate theme park that is Bali – and the locals who work in tourism have swiftly learnt how to keep the vacationers coming back year after year and bringing along more friends.

The entire world is drawn to the ultimate theme park that is Bali – and the locals who work in tourism have swiftly learnt how to keep the vacationers coming back year after year and bringing along more friends.In Bali you don’t get the sense of pseudo-morality and fuddy-duddy judgmentalism that puts a damper on folks having fun any way they want – young Aussies who blow their wad going from beach to beach in quest of the ultimate wave, consuming beer by the crate in the process, are as welcome as earnest ethnomusicologists, culture vultures, or the rich and retired. Wherever I stopped for coffee or a bakso fix, some old chap would question why I was traveling solo instead of with a nice chewet (Balinese for "girl"; boys are called chowok). "Don't be putting ideas in my head," I'd quip and this would generate a fair bit of mirth and merriment. How refreshingly unprudish the Balinese are!

You feel welcome in Bali, regardless of your holiday budget. And the range of options is vast – you can spend anything from 30,000 to 3,000,000 rupiahs on a night’s accommodation. Chances are you’ll have a great time either way.

How did the Balinese accomplish this extraordinary feat of embracing modernity with a broad grin while retaining traditions that sustain social cohesiveness? Perhaps a significant clue can be found in the nature and personality of their prime deity, an emanation of Shiva-Natarajah they call Tintya, usually portrayed as an agile and elvish figure – sometimes painted with energy bolts shooting from every joint, often supported on a spinning chakra (disc or wheel), but invariably dancing the cosmic dance of primordial energy.

How did the Balinese accomplish this extraordinary feat of embracing modernity with a broad grin while retaining traditions that sustain social cohesiveness? Perhaps a significant clue can be found in the nature and personality of their prime deity, an emanation of Shiva-Natarajah they call Tintya, usually portrayed as an agile and elvish figure – sometimes painted with energy bolts shooting from every joint, often supported on a spinning chakra (disc or wheel), but invariably dancing the cosmic dance of primordial energy.Studying images of Tintya through modern eyes, one might be tempted to speculate that the supreme deity of the Balinese was modeled after a visiting ET!

Consider the descriptive names the Balinese have for Tintya: he’s also known as Sangyang Widi (The Wise One), Sangyang Licin (The Elusive One), and Sangyang Tunggal (The Absolute One). Interestingly, Tintya represents the Supreme Embodiment and Manifestation of Life Itself in its unfathomable entirety and infinite diversity. Tintya is revered in Bali above the trinity of the exoteric Hindu pantheon, viz., Brahma, Vishnu, and Shiva.

Exploring the outskirts of Ubud on my motorbike, I stopped by another sacred fig tree and entered the small pura beside it. The stone walls and floor of the pura were green with ancient slime and the place looked fairly unvisited. Then I spotted an incongruously modern steel ladder bolted to the central candi (or shrine). Ascending the ladder between a pair of guardian dragons carved in stone, I came face to face with a Tintya icon, freshly gilded and radiant in the bright sunshine.

Exploring the outskirts of Ubud on my motorbike, I stopped by another sacred fig tree and entered the small pura beside it. The stone walls and floor of the pura were green with ancient slime and the place looked fairly unvisited. Then I spotted an incongruously modern steel ladder bolted to the central candi (or shrine). Ascending the ladder between a pair of guardian dragons carved in stone, I came face to face with a Tintya icon, freshly gilded and radiant in the bright sunshine.This was truly an unexpected epiphany which triggered a flood of long-buried genetic memories, too complex and mysterious to elaborate upon in a blogpost. Someday I may find a way to express these antediluvian flashbacks in words. But for now, suffice to say that I remembered the origins of the gods and the beginnings of religious indoctrination on this exquisite (and soon, soon to be liberated) holographic planet.

|

| Terima kasih, Bali. I thank you with all my heart for staying true to yourself. |

Text & photos © Antares